Copyright Challenges in the Age of AI – Part 2

Meet The Authors

Olli Pitkänen

CLO

Dr. Olli Pitkänen is proficient expert with extensive experience in ICT and law, leading multidisciplinary projects and providing expertise in legal aspects of ICT, IPRs, privacy, and data as a founder of an IT law firm and advisor to companies and the Finnish government.

Sami Jokela

CTO

Dr. Sami Jokela is a seasoned leader with 20+ years of experience in data, technology, and strategy, including roles at Nokia, co-founding startups, and leading Accenture’s technology and information insight practices.

Waltter Roslin

Lawyer

Waltter is a lawyer focusing on questions concerning data sharing, governance, privacy and technology. He is also a PhD researcher at the University of Helsinki where his research focuses on the Finnish pharmaceutical reimbursement scheme.

Copyright challenges in the age of AI - Part 2: Is the output of a generative AI system copyrightable and who is the author?

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) presents new challenges in the copyright system.

In the previous part, we analysed these challenges and show how they appear from the perspectives of developing and using AI systems. Especially, we noted that depending on the algorithm, machine learning process can be copyright relevant. If the training involves copying the creative choices made by the original author of a copyrighted work in the training data, it could violate the author’s exclusive rights. On the other hand, if the machine learning process can be considered as data mining, it can be within the limitation or exception defined in the DSM directive and therefore lawful within the EU. Yet, if the output of a generative AI system includes copies of the works in the training data, that cannot be justified by that limitation or exception.

In this second part of our three-part posting on these challenges we discuss the authorship of AI generated output.

Authorship

According to copyright law, the author is the person who created the work and who originally holds the copyright to it. Often copyright is transferred directly to the employer by law, or it may be transferred to a publisher, for example, but the original creator is still to be regarded as the author. As the role of AI grows, questions arise as to who is the author of a work that has been influenced by AI?

As discussed in the previous section, to qualify for copyright protection, a work must be original, the author’s own intellectual creation. The author must have made creative choices in creating the work.

If AI is used in a process that produces something that is perceived as creative, there are several possibilities as to where the creativity comes from.

First, the AI user can use the system in a creative way. This is often the case today, for example, when a software product such as Adobe Photoshop contains several tools incorporating AI technology. When editing images in Photoshop, these AI tools can enable complex editing , but in most cases the choices are still made by the human user of the software.

Second, the software developer may have made creative choices that affect the output of the system in such a way that it seems creative no matter how it is used.

Third, an AI system can be based on a general model trained using data that includes creative works such as newspaper articles, novels, compositions, pictures or paintings. Likewise, data used to refine a model for a specific application may contain similar works. As discussed in the first part, it is possible that the creative choices made for these works are also reflected in the output produced by the system. Thus, the creativity of the output can be traced back to the original authors of the training material.

So, an AI output that appears creative may in fact be the result of creative choices made by different actors. Actually, it is often a combination of several individuals creativity, which is called joint authorship in the copyright law. Unless the authors have assigned their rights or agreed otherwise, the consent of all of them is required for commercial exploitation of the joint work, which can be quite complex.

Currently, most definitions of originality require a human author. Thus, AI cannot at the moment be considered as an author. Yet, a good question is, should an automatically generated work be copyrightable, in the first place? While exclusive rights such as copyright can motivate people and companies to research, create and invent new, useful goods, they can also set up monopolies that are harmful to society and the economy. Therefore, careful consideration should be given to whether granting exclusive rights to automatically created works is societally desirable. If yes, who should get the copyright?

Some believe that one day it will be necessary to grant rights to AI itself. This would probably require some AI systems to achieve legal personhood. However, at the moment it is very difficult to see what problems this would solve.

Observable originality

One of the key principles behind the copyright system is that copyright does not require a filing of an application and an official examination process like patents. Instead, everybody should be able to evaluate a work and just by observation assess whether it is original and thus copyrightable. In practice, that can be difficult even for an expert, but in principle anyone can read a text or listen to a piece of music and tell if it is copyrightable or not.

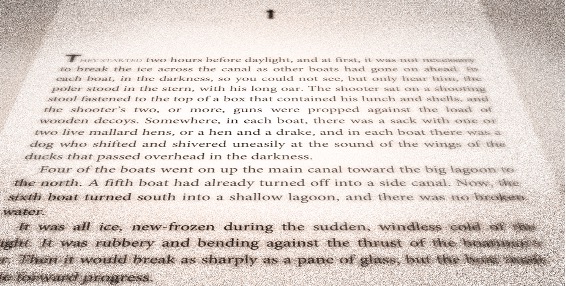

Ernest Hemingway: Across the River and Into the Trees

Technological development has already challenged that. From a photograph, it can be impossible to tell if the photographer has made creative choices while producing the image, or if the picture is merely a random snapshot. The application of AI makes it ever more difficult to evaluate the copyrightability of a work only by observing the end-result. For example, if an image were a painting by a human artist, it would be protected by copyright, but if it was automatically generated by an AI system, it would not. Therefore, the problem is that in the future we shall need more information about how works are created to assess their copyrightability, which seriously confronts the basic principle of copyright regime. Shall we need a new intellectual property right between copyright and patent that would protect originality and creativity like copyright, but would require an application-based prior prosecution before an authority officially grants the right?

|

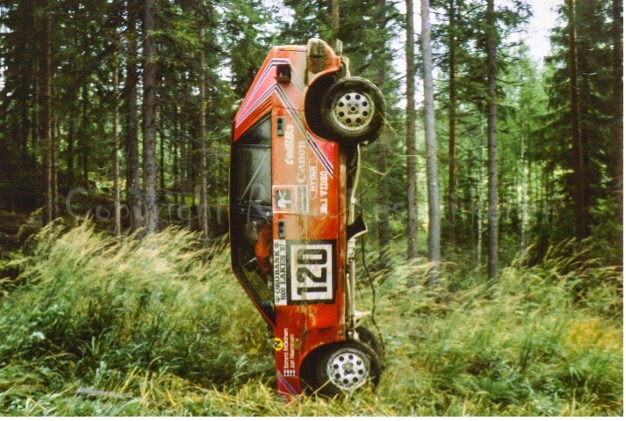

Reijo Keskikiikonen: Tommi, Copyright Council 2016:4, https://okm.fi/lausunnot-2016 Is this a copyrightable work – or merely a random snapshot? Did the photographer make creative choices? Impossible to tell, if we don’t know, how the picture was produced. In this case, the Copyright Council considered that the key element of the photograph is the successful timing of its taking, but this alone is not sufficient to make the picture independent and original. Therefore, it is not copyrightable. However, the photograph still has more limited protection under the photographer’s neighbouring right under Finnish copyright law. |

Neighbouring rights

Another problem area of the copyright system in relation to technological developments is neighbouring rights. They are similar to copyright but are to some extent weaker rights and do not require a threshold of originality to be exceeded. In Europe, for example, the Copyright Term Directive (Directive 2006/116/EC) allows Member States to provide for the protection of photographs other than those that are sufficiently original to qualify for copyright protection. Therefore, in many European countries, non-original photographs are protected by a neighbouring right, often called the photographer’s right. Similarly, producers of sound and image recordings – music, television and film – are granted protection for their recordings, but producers of games or events, for example, are not. Anyone who takes a photo shall have a right, but a drawing needs to be original before it is protected. It seems generally quite random when something is protected by a neighbouring right and when it is not. If anything, a common factor behind the complexity of neighbouring rights might be a tendency to protect investments in intellectual property. [1]

The main difference between copyright and related rights is that the latter do not require creative choices. The development of artificial intelligence makes these limited rights even more ambiguous, as digital convergence blurs the boundaries between artificial classifications: is there any difference between a photograph edited by AI and a non-photograph produced by AI? Why should some be protected and others not?

The Anglo-American copyright tradition tends to emphasise the economic aspects of copyright, such as the right of authors to benefit financially from their creativity and the relatively wide scope for employers to obtain rights to works created by their employees (“contract for services” in the UK or “work for hire” in the US). In the continental European tradition, particularly in France, more emphasis is placed on the droit d’auteur, i.e. the moral rights of the original author to his creation. Most jurisdictions fall somewhere between these two extremes and seek to balance the interests of creative individuals and paying commissioners.

As noted above, at least some neighbouring rights seem to protect in particular investments in intellectual property. The economic aspects of copyright may have a somewhat similar rationale: an author who has invested time, skill and creativity, or an employer who has paid a salary to an employee, should benefit from the work. It could therefore be desirable to move the copyright system in the direction of giving the one who has invested in the system the right to works created with the help of AI.

Conclusions

To conclude this second part, the results produced by an AI system may well fall outside the scope of copyright protection, because the author must be human. However, the originality of the results of a generative AI system can be traced back to the creative choices made by the user, the software developers, the authors of the works in the training material – or any combination of these. Some neighbouring rights, such as photographer’s or producer’s rights, may also apply to works produced by an AI system.

In the third part, we’ll present our ideas on copyright and other rights in AI models.

1001 Lakes’ experts are happy to discuss these topics with you if you have concerns of AI and copyright or how to develop and use AI in compliance with the copyright law.

[1] Pitkänen, O.: Mitä lähioikeus suojaa? [What is protected by neighbouring rights?] Lakimies 5/2017, p. 580–602.